Game Theory Overview

1. Definition

Game theory is the study of how individuals or groups make decisions when their choices affect one another. In situations of conflicting interests, it provides a mathematical framework to identify both the best possible outcomes overall and the rational strategies for each participant (Carl, 2021).

The theory is built on two key assumptions. First, players are considered rational actors: every individual or group is treated as a “player” whose goal is to maximize their own benefit, whether by gaining advantages or minimizing losses. Second, each decision is guided by the principle of rational choice, meaning that before acting, a player carefully evaluates the potential gains and risks of their decision.

In practice, Game theory examines decision-making through four main elements: the information and preferences of the players, the strategies available to them, the interactions among these strategies, and the payoffs or outcomes that result. Together, these components shape the structure and analysis of any given game.

Game theory is generally divided into two categories. Cooperative games are those in which players can form binding agreements and coordinate strategies, while non-cooperative games are situations where agreements are not enforceable and must instead rely on self-interest (Sajedeh, 2020).

From a broader perspective, scholars also distinguish between two forms of rationality. Individual rationality refers to situations where each player maximizes their own payoff without considering collective outcomes, as seen in the classic example of the Prisoner’s Dilemma. In contrast, collective rationality emphasizes the pursuit of mutually beneficial, “win–win” solutions that balance individual interests with group welfare

2. Historical Development

2.1 Early Contributions

The earliest known reference dates back to 1713, when Charles Waldegrave analyzed the card game le her. His solution to a minimax mixed-strategy problem in a two-player version of the game is now recognized as the Waldegrave problem.

In 1838, Antoine Augustin Cournot introduced a model of oligopoly competition in his work Researches into the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth. His solution—later identified as a form of Nash equilibrium—was criticized by Joseph Bertrand in 1883 for being unrealistic. Bertrand proposed an alternative model of price competition, which was further refined by Francis Ysidro Edgeworth.

In 1913, Ernst Zermelo published one of the first formal mathematical analyses of strategy in chess, applying set theory to demonstrate the concept of an optimal strategy (On an Application of Set Theory to the Theory of the Game Of Chess).

2.2 Establishing the Field

The modern foundation of Game theory was laid by John von Neumann. His 1928 paper, On the Theory of Games of Strategy, introduced the use of Brouwer’s fixed-point theorem in analyzing strategic interactions. This work culminated in the influential book Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944), co-authored with Oskar Morgenstern, which formalized utility theory and provided systematic methods for analyzing two-person zero-sum games.

Around the same time, Émile Borel made important contributions with his book Applications aux Jeux de Hasard (1938). He proved a version of the minimax theorem for symmetric two-person zero-sum games and analyzed the so-called Blotto game. Although he initially conjectured that mixed-strategy equilibria did not exist in finite games, this was later disproven by John von Neumann.

A major breakthrough came in 1950, when John Nash introduced the concept of the Nash equilibrium. Unlike von Neumann and Morgenstern’s work, Nash’s equilibrium applied to a broader range of games, including non-zero-sum and n-player non-cooperative games. His proof that every finite game has at least one equilibrium in mixed strategies transformed the field.

During the 1950s, Game theory expanded rapidly. Key concepts such as the core, extensive-form games, fictitious play, repeated games, and the Shapley value were developed. The decade also marked the first applications of Game theory to philosophy and political science. It was during this period that the famous Prisoner’s Dilemma was formally analyzed, through experiments conducted by Merrill M. Flood and Melvin Dresher at the RAND Corporation, where interest in Game theory was driven by potential applications to global nuclear strategy.

2.3 Growth & Recognition

The development of modern Game theory is closely linked to a number of landmark works and Nobel Prize–winning contributions. The foundation was laid by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern with Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944), which established Game theory as a formal discipline. Building on this, John Nash introduced the concept of the Nash equilibrium in his influential papers (1950–1951), showing that every finite game has at least one equilibrium in mixed strategies.

In the 1960s and 1970s, further refinements followed. Reinhard Selten developed the concepts of subgame perfect equilibrium (1965) and trembling hand perfection (1975), while John Harsanyi introduced the theory of incomplete information in Games with Incomplete Information Played by “Bayesian” Players (1967–1968). At the same time, John Maynard Smith applied Game theory to biology in Evolution and the Theory of Games (1982), formulating the concept of the evolutionarily stable strategy

3. Type of games

A game is cooperative if the players are able to form binding commitments externally enforced (e.g. through contract law). Cooperative games are often analyzed through the framework of cooperative Game theory, which focuses on predicting which coalitions will form, the joint actions that groups take, and the resulting collective payoffs. Cooperative Game theory provides a high-level approach as it describes only the structure and payoffs of coalitions (R. Chandrasekaran, 2016)

A game is non-cooperative if players cannot form alliances or if all agreements need to be self-enforcing (e.g. through credible threats). Non-cooperative Game theory which focuses on predicting individual players’ actions and payoffs by analyzing Nash equilibria. Moreover, non-cooperative Game theory also looks at how strategic interaction will affect the distribution of payoffs (Ritzberger, 2003)

In Game theory, a symmetric game is a game where the payoffs for playing a particular strategy depend only on the other strategies employed, not on who is playing them. If one can change the identities of the players without changing the payoff to the strategies, then a game is symmetric. Symmetry can come in different varieties. Ordinally symmetric games are games that are symmetric with respect to the ordinal structure of the payoffs. A game is quantitatively symmetric if and only if it is symmetric with respect to the exact payoffs. A partnership game is a symmetric game where both players receive identical payoffs for any strategy set. That is, the payoff for playing strategy a against strategy b receives the same payoff as playing strategy b against strategy a. (Shih-Fen Cheng, 2004)

4. Examples

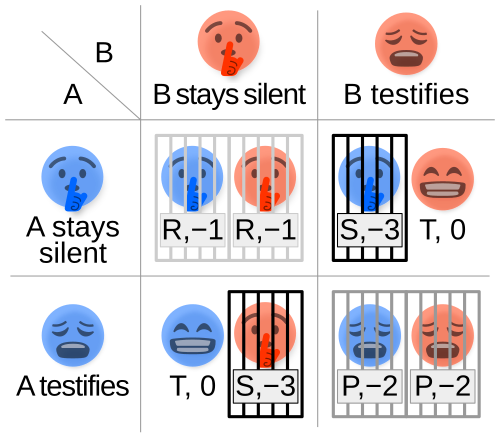

The best example of Game theory is a classical hypothesis called “Prisoners Dilemma”. According to this situation, two people are supposed to be arrested for stealing a car. They have to serve 2-year imprisonment for this. But, the police also suspect that these two people have also committed a bank robbery. The police placed each prisoner in a separate cell. Both of them are told that they are suspects of being bank robbers. They are inquired separately and are not able to communicate with each other.

The prisoners are given two situations:

- If they both confess to being bank robbers, then each will serve 3-year imprisonment for both car theft and robbery.

- If only one of them confesses to being a bank robber and the other does not, then the person who confesses will serve 1-year and others will serve 10-year imprisonment.

According to Game theory, the prisoners will either confess or deny the bank robbery.

So, there are four possible outcomes :

Figure 2: Payoff matrix of the Prisoners’ Dilemma

(Source: Wikipedia, “Non-cooperative Game theory”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Non-cooperative_game_theory)

Here, the best option is to deny. In this case, both will have to serve 2 years sentence. But it cannot be guaranteed that others would not confess, therefore most likely both of them would confess and serve the 3-year sentence.

References

- Carl-Joar (2021). Game theory and applications —connecting individual-level interactions to collective-level consequences https://research.chalmers.se/publication/527311/file/527311_Fulltext.pdf

- Sajedeh Norozpour and Mehdi Safae (2020). An Overview on Game theory and Its Application. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/993/1/012114/pdf

- Heinrich H. Nax & Bary S.R. Pradelski (2020).Introduction to Game theory- Lecture Notes 02-game-theory.pdf

- R. Chandrasekaran,(2016). “Cooperative Game theory” cooperative-game-theory-rev.dvi

- Ritzberger, K. (2003). Foundations of Non-Cooperative Game theory. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics JITE, 159(3), 601. https://doi.org/10.1628/0932456032954792

- Shih-Fen Cheng, Daniel M. Reeves, Yevgeniy Vorobeychik, Michael P. Wellman 92004). “Notes on Equilibria in Symmetric Games” https://strategicreasoning.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/notes-symetric.pdf#:~:text=A%20game%20in%20normal%20form%20is%20symmetric%20if,provide%20a%20formal%20definition%20in%20the%20next%20sec-tion.%29

- Yin, Q., Yu, T., Feng, X., Yang, J., & Huang, K. (2024). An Asymmetric Game Theoretic Learning Model. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 130–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-97-8502-5_10

- Ilan Adler (2012), The equivalence of linear programs and zero-sum games, International Journal of Game theory.

- Master Class (2022).Zero-Sum Game Meaning: Examples of Zero-Sum Games Zero-Sum Game Meaning: Examples of Zero-Sum Games – 2025 – MasterClass

- Brocas, I., Carrillo, J. D., & Sachdeva, A. (2018). The path to equilibrium in sequential and simultaneous games: A mousetracking study. Journal of Economic Theory, 178, 246–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jet.2018.09.011

Dig deeper into Stable Matching

Game Theory

MIT 14.16 S16 Matching Theory Lecture Slides

Comprehensive matching theory course materials from MIT covering fundamental concepts, solution methods, and applications across economics and strategic analysis.

2.11.2 Matching Ritual: Video

Video lecture exploring matching rituals and algorithms with practical examples and interactive learning approaches for understanding matching theory.

Definition, Facts, & Examples | Britannica

Authoritative encyclopedia entry providing clear definitions, historical context, and real-world examples of game theory applications.

Stable Matching

Generic Algorithm